THE MOMS SAID IT WAS RIGHT FOR ADANTE AND HIS SISTERS TO LIE ON THE COLD BASEMENT FLOOR WITH THE EYE MASKS AND NO BLANKETS. They said that not having supper, breakfast or lunch would teach them a lesson. They said homeschooling was better, that being out in the world corrupted a person, that regular school didn’t embrace brown kids. They said the neighbors didn’t like brown kids either and were all homophobes.

Adante didn’t even have the hat anymore. The Moms had taken it, which they wouldn’t admit. None of his sisters had taken it. A hat could only get to so many places when you were living most all your hours in a house at the end of a dead end road with the nearest neighbor a five minute walk through woods, across fields, and hopping fences. Which Adante liked that part. Actually they had lived at the dead end house until two days ago, when the Moms shook all of them awake and said they needed to go.

Was it because they were behind on rent, because Adante had talked to Fred and Melissa about food? Maybe it was because the Moms wanted to trade some of Adante and Janay’s finger-knitting crafts or Mom Gina was going to tell her poetry, or because there was a peace action at the border.

Now they were two days in, with one stop at the pharmacy and stops every day at the gas station and not always off-grid small ones and eating gas station food, and sometimes picking up liquor and paying with the credit card, which was supposed to be for emergencies, and no stops at the barter fair.

On the van they had a “Why Be Normal” bumper sticker and a “Keep Portland Weird” sticker. They had stickers of space aliens—two full-sized female aliens in triangle skirts, then a line up of five shorter aliens—Adante, Janay, and the three younger ones. They had a sticker that read “Sustainable Fun,” which wasn’t what they were having. Nobody laughed. Not even when Adante farted after eating his donut which Mom Beth handed out after a gas station stop.

So far they weren’t even fake camping. Fake camping meant sleeping in the van, but at a camping place, not just pulling into a Walmart lot for an hour.

Mom Beth said it was because they were in Trump Country. White people land big time.

Until he was about twelve people smiled, but then his limbs grew long and he started packing on muscle and his voice changed. Lying in the basement on the concrete and even missing meals wouldn’t cure becoming what white people feared: a full-grown black man. At least he could hide that springy hair under a hat. Or could have. If the Moms hadn’t taken it.

Mom Gina drove. Mom Beth took pills out from an orange bottle. The Moms popped the pharmacy drugs like candy. Doing it in the open, not even trying to hide it. Saying the pills were different from the big pharma evil ones.

No enrichment was happening. No radio, no motivational CDs, no Spanish lessons, no yoga relaxation, no Rick Hansen talks. The Moms seemed done trying to improve them. Maybe they were good enough now.

“We want you where we can see you,” Mom Gina said at the Citgo. Stay in sight of the Moms. But it wasn’t all bad. Like today, everyone got an energy bar for breakfast. They got however much water they wanted. The Moms let things get to a comfortable temperature on the AC.

Even so, all of them stank and needed showers.

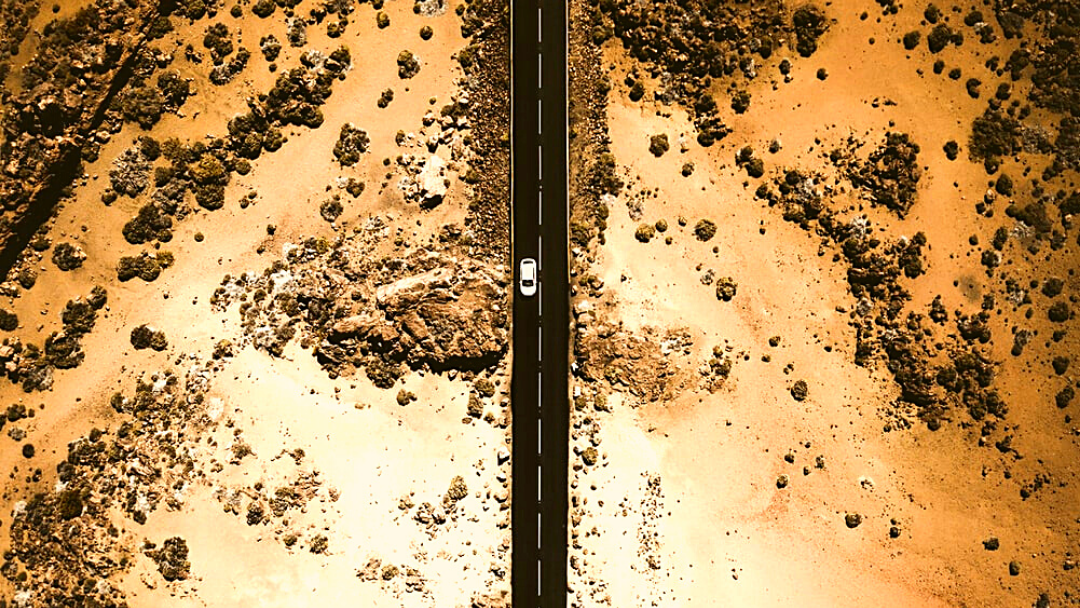

Things passed—the fields, the brown blankness, the mountains.

They weren’t talking plans to join in a protest march at the border. They weren’t saying anything about Immigrants’ Rights or Black Lives Mattering. They weren’t practicing songs. They weren’t doing role play exercises about what to do if they got stopped by law enforcement. Mom Beth hadn’t opened the craft bag and distributed the markers and the colored construction paper to make posters. Adante would have drawn a fist rising up to the sky.

He knew geography pretty well from google maps. In Minnesota, when he and Janay had learned at regular school, he knew it from globes and maps in books. He wondered if he and Janay knew enough Spanish and other survival skills to live in Mexico.

The Moms used to wrap their arms around Adante and say what a miracle it was that Gaia had allowed them to come together. That was before Washington and Oregon and lying on the concrete basement with the masks on.

Janay cried and he signed “I love you” in her palm. He told himself the Moms only did tolerable bad things. They did what they did to turn Adante good. Wasn’t he already good? Didn’t the Buddha say that? Didn’t Rick Hansen say that?

You’ll never be normal. You’re fucked up. You came from fuck ups and were delivered to fuck ups. Mom Gina said those things with her hair on end, her teeth bared, her neck cords popping, and tears streaming down her red face.

That stuff he didn’t take in. That stuff he refused and went elsewhere. They could say “Lie down in the basement with your mask on. Naked. With your clothes off. No blanket. No dinner. No Clif Bars. No tooth brushing.” The punishment could mean even teeth cleaning wasn’t allowed. But he wouldn’t take in that he was garbage.

The land rose and fell, the wind blasted in his ears, the semis rumbled. State Troopers aimed their radar guns from their little dens at the highway turn-arounds and he sat up straight, with his hands in his lap, like the Moms had taught. For safety. Brown people had to behave and having white people in the car wouldn’t necessarily save you. Even if you were extra good, the next thing you still might be face down in the pavement with a knee in your back, then in a jail cell with a belt around your neck, then with your jailers cutting you down from the rafters.

He and Janay talked in nudges and shoulder shrugs; pictures with their hands when the Moms weren’t looking. He told himself they were going to visit some of Mom Beth’s friends, that they were still doing normal stuff. Or stuff that was normal for other people. Getting gas. Buying Doritos and beef jerky at Sinclair.

The night he ran to Fred and Melissa’s for food, they didn’t point a gun at him. They sat Adante on the couch. Fred put more wood on the fire. Melissa draped a blanket over Adante’s shoulders. Fred and Melissa’s big furry dog licked the back of Adante’s hand. Melissa brought him toast, with cream cheese, jam, and peanut butter. Adante wolfed it down and Melissa went out to the kitchen to make more.

Adante ate half the block of cream cheese, a quarter of the peanut butter jar, the rest of the jam. He wanted to apologize, but Melissa said he didn’t need to apologize for being hungry. He was embarrassed for being so weak. Melissa and Fred said just coming here tonight was strong.

Even though he smelled of pee and body odor and basement, Melissa hugged him. Fred winced and a pain came into Melissa’s eyes when Adante said how old he was. He shouldn’t have said sixteen. He should have lied and said fourteen.

He didn’t want to get off Fred and Melissa’s couch, but his clothes might pick up the fire smell and some nights Gina patrolled.

Mom Beth passed around Swiss Miss. A special treat, but Adante only pretended to drink it. He’d done pretty much all the Moms had said to do until then; he’d believed pretty much everything they had said.

Janay and the three younger ones drank the Swiss Miss and fell asleep. Adante faked sleep.

A plastic bag flew out from a shiny white Lexus. The bag careened over the roofs of the cars. Didn’t the Lexus driver know plastic wound up swirling in the ocean, tempting whales or smaller creature to swallow it and die? He waited for Mom Gina to throw up her hands and say God damn one percenter ruining the countryside.

“There’s us,” Mom Beth said instead.

Meaning the plastic bag? Meaning they were what was discarded?

* * *

“I want to call my brother,” Mom Beth said. “Just let me do that, please.”

“Go fucking right ahead,” Mom Gina said. “You know where the phone is.”

Adante slit his right eye open. Mom Beth had a brother?

“That phone is dead,” Mom Beth said.

Mom Gina kept driving.

“I want to talk to him,” Mom Beth screamed.

Adante’s sisters slept. Alcohol mixed with the Moms’ body odor and came out in their sweat.

Adante poked Janay. Nothing. He poked again. Zero stirring.

Mom Beth didn’t say let’s get a charger, let’s get a battery for the phone.

Mom Gina didn’t say Beth could call her brother tonight. “This is what we agreed,” Mom Gina said. “We came up with all the reasons why.”

Mom Beth looked toward the back seat.

Adante shut his eyes. Quick.

“I wanted them to be happy.” Mom Beth’s voice was cracking.

Adante kept his eyes closed. She might still be looking.

Time passed in the movement of the wheels and in his bones.

Mom Gina ruled. If Mom Gina said concrete floor and eye masks, eventually Mom Beth buckled and concrete floor and eye masks was what they did.

He slit his eye open. They were up high, on cliffs. He glimpsed ocean below. The trees and cliffs were in shadows. Everything gray and not quite sunrise.

Janay leaned on him, heavy, breathing deep. He poked Janay’s thigh, poked between her ribs. Nothing. He couldn’t wake her.

The van sped, slowed. Mom Gina knuckled the steering wheel. She swung the van right, then left. She wove back and forth over the center line. He should have waved at the state trooper. He should have flipped him off and taken his chances. Mom Gina wasn’t sleepy or drunk. She thought the world was crap and the future was crap, but it was the only world Adante had. His life mattered now.

Mom Gina backed up to the shoulder. She pointed the van so it nosed outward, across the highway’s center line, towards the ocean. The lookout spot was directly in front of them. There was room for lots of cars, but nobody was parked.

Mom Beth reached for the keys. Mom Gina shoved her away. Adante popped his and Janay’s seat belt release buttons. Mom Beth slammed against the passenger door. The door locks clicked.

“Let him out. Let the boy out. Let one of us be saved,” Mom Beth screamed.

Adante leapt forward and reached for the wheel. Gina elbowed him back and hit the gas. Adante felt the speeding, the rushing forward. The seatbelt alarm chimed.

“Let the boy out!”

Adante threw his weight against the door, his left hand pressed on the lever. He gripped Janay by the arm. Mom Beth screamed or maybe it was him. Out the windshield the sky was opening, getting larger. He threw his weight against the door again.

The metal door slid back, along the metal track. He and Janay hurtled through the opening, into damp, misty, sun-washed morning air. They skimmed across sharp rocks. Gravel cut through their clothes and abraded their skin. The van shot through the metal barrier, disturbing a flock of birds which funneled up into the sky. Then came the thump and thunk of the van, bumping and booming downward, the shrieking gulls and surf.

He covered Janay with his arm. His palms pressed into the pebbles, his toes dug into soft earth. He buried his face in Janay’s shoulder, gasping. He felt hollowed out, but ready and strong. He wept for what had been taken away and for what he had been given.

When Janay awoke, they hitched toward Mexico.

Like what you’re reading?

Get new stories or poetry sent to your inbox. Drop your email below to start >>>

OR grab a print issue

Stories, poems and essays in a beautifully designed magazine you can hold in your hands.

GO TO ISSUESNEW book release

I’ll Tell You a Love Story by Couri Johnson. Order the book of which Tim Jeffries said, “Surprising in their originality, filled with broken wisdom, and with a refreshing use of language and imagery, these are stories to savour and mull over one at a time but which add up to a satisfying whole.”

GET THE BOOK